Insights

Feb 25, 2020 _ insights

Milieu: Creating Restorative Environments in Behavioral Health

Every setting cues us how to behave. Is it loud and active? Quiet and intimate? Cozy or spare? Modern life bombards us with stressors. When we need services to help us cope with a mental illness, or life crisis, the design of behavioral health settings matters.

It’s time to take a closer look at the collection of therapeutic settings known as milieu. In a behavioral health hospital or long-term residential care facility, these settings foster social interactions and activity, and it’s where inpatients and residents spend their day since time alone in bedrooms is usually limited to sleeping, dressing, or perhaps an hour of quiet time. Milieu is used for group therapy sessions, guided activities, dining, and free choice time. While most facilities provide milieu ranging from highly controlled unit spaces to education or recreation areas common to the building, creating enriching spaces that offer social choices and reduce aggressive behavior are key to successful milieu design. Done right, these spaces can restore a sense of normalcy during a vulnerable time; de-stigmatize an institutional experience and be restorative.

Nearly one in five adults suffers from a behavioral health condition and may at some point require periodic hospitalization or extended treatment at a long-term residential care facility. A 2018 article from The Advisory Board documents the surging demand for these services, and how the shift to a population health model of care is leading to more or expanded facilities.* Most of a patient or resident’s day is spent in milieu spaces—whether within the unit or off— they should empower and facilitate recovery, not impede it. As we face the prospect of building more, it is imperative that we think about the impacts of these spaces, and how they can be positive, empowering, and healing

THE SAFETY CONUNDRUM: DENSITY IMPACTS AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR

On or off- unit, design of safe and restorative milieu space presents a unique challenge.

Units typically have just two or three staff per shift. Inpatients and residents are never permitted to be alone in any milieu space, so an individual’s use of a private milieu space (such as a de-stimulation room) requires staff to accompany them, resulting in less staff to supervise the open milieu. Patients are encouraged to remain in communal spaces where staff can visualize all parts of the room in order to respond quickly to problems and signal colleagues if they need help. While logical from a risk management standpoint, it has an opposite effect on the person being treated. These patients and residents are in an extremely vulnerable state and feel out of control of themselves and their situation. Being exposed—and given no choice but to interact with other strangers—they don’t perceive themselves as being safe.

Even if no negative incidents occur, the person experiences a heightened state of anxiety. But negative incidents do occur. Dominant personalities can create conflict or encourage negative/destructive behaviors by those trying to avoid conflict. Units of as many as 12-16 individuals sharing one room can heighten social friction. A study conducted by Roger Ulrich and Lennart Bogren on how design can influence aggressive behavior, links crowding to a rise in aggression. Their research recommends a unit social density (number of persons per room) of less than .5 patients per room available (counting bedrooms, private bathrooms and all unit milieu). **

SOCIAL NEEDS ARE NOT ONE SIZE FITS ALL

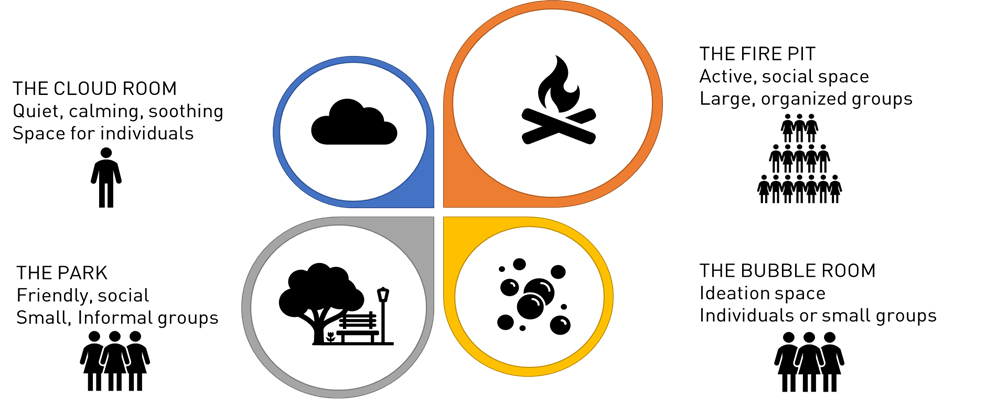

Social choice is a critical consideration for successful milieu space. Introverts and extroverts have very different needs. For introverts, time alone helps them restore and reset. Denying them time alone creates exhaustion and stress. Extroverts are energized by social interaction and are more likely to seek attention and may become aggressive or frustrated if rebuffed. Additionally, someone processing difficult emotions may desire privacy; someone who feels tired and cranky may want to be left alone. Someone engaged in a small group conversation may not welcome a newcomer to the group.

DESIGNING A PATH TO BETTER HEALING

GBBN’s approach to behavioral health incorporates much of our research into health-generating spaces. We use the built environment to reduce stress and build confidence so that treatment can be more effective and destructive or aggressive behavior reduced.

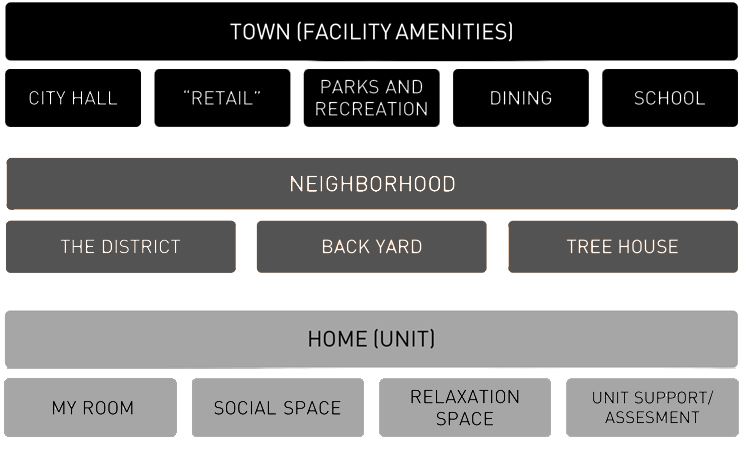

Our approach to milieu establishes normalcy by creating an analogy to everyday life. We think about milieu in three tiers and advocate a variety of milieu spaces at each level. This begins with evoking home (the unit) with access to broader amenities of a “neighborhood” (group of units) and functions of a town (facility-wide amenities). Much like a home, individuals have their bedroom, and multiple spaces for other activities of daily life, as well as therapy and critical intervention space. The neighborhood offers therapy areas, physical activity rooms, even a kitchen and outdoor areas. At the town level, offerings expand to include things like outdoor recreational and therapy areas, a gym, “restaurant” (cafeteria), and “retail” spaces such as a health clinic, hair salon, or store where goods such as sleepwear or slippers can be purchased. Some individuals may be restricted to the unit upon admission, but they can look forward to greater freedom and autonomy as they progress and unlock access to the neighborhood, and then the town spaces.

A biophilic approach incorporates calming color schemes, lighting at the correct color temperature throughout the day to maintain the circadian cycle, access to outdoor spaces at the neighborhood level, and natural light in all milieu spaces.

We also consider ways to deliberately empower individuals. Bedrooms feature a variety of lighting options, and places to draw or display personal items. Different milieu spaces on the unit offering different activities and atmospheres let people choose how to spend free time. Movable furniture and different seating options allow customization to meet individual or group needs.

Feeling safe and being able to control one’s socialization are critical to recovery. We address this by creating occupiable edge conditions such as benches along a wall or shallow alcoves that allow newly admitted patients or residents to acclimate gradually; they can be present in a space, without being forced to socialize. Introverts also appreciate this opportunity to be alone or in a small group, and staff can establish trust by building one-on-one relationships that don’t feel forced.

Finally, by looking at our unit as a home, we can leverage different social dynamics. This makes time spent on the unit less monotonous and allows the unit population to be broken-up into smaller groups, which reduces aggressive behavior. We think about these spaces as being of various sizes; of looking and feeling different based on the activity. Because staff visualization is important, these spaces can be partially enclosed and employ finish changes to denote the change in space (for example, lower ceilings in small group areas to make them feel more intimate).

The stress response can be neutralized by providing a variety of positive distractions such as artwork that has strong foreground, middle ground, and background and is of recognizable settings; or tactile pieces that encourage interaction. Opportunities for pacing, rocking, or other repetitive movements can help soothe agitation. Gross motor rooms, where patients or residents can release energy can also help them remain calm in social groups.

Designing space for a diverse population suffering from a range of mental health problems is a challenge. It involves deliberate work to avoid environments that will exacerbate the effects of trauma and help individuals feel respected and empowered.

*“How Healing Design Can Overcome the Security-Comfort Tension in Behavioral Health Facilities,” Advisory Board, 2018

**Roger S. Ulrich, Lennart Bogren, Stuart K. Gardiner, Stefan Lundin, “Psychiatric Ward Design Can Reduce Aggressive Behavior,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 57, (2018): 53-66

2018